Of Light and Shadow: The Beautiful Nothings

Dedication

This body of work is dedicated to the dreamers and people who have worked tirelessly to find a voice, even a whisper, amongst all the loudest of flowers and the harshest of light. For the child inside us all.

What do a glasshouse, a diorama, and a camera have in common?

Of Light and Shadow is a four part exhibition that took place on March 22, 2024 in the SIU Communications Building Northlight Studio. The work included installation art and performance. One of the key components of this historical moment in Of Light and Shadow is the way in which the concept of interior and exterior collide when discussing the architectural and natural components present in glasshouses. In other words, glasshouses are an abnormality in the distinction between indoors and outdoors. Through combining social practices with horticulture, glasshouses and Wardian cases invade the domestic interior and blur boundaries between the interior and exterior. Glasshouses and Wardian cases exist as worlds within worlds made up of pieces of places and times in environments where they are not natural—an artificial anomaly.

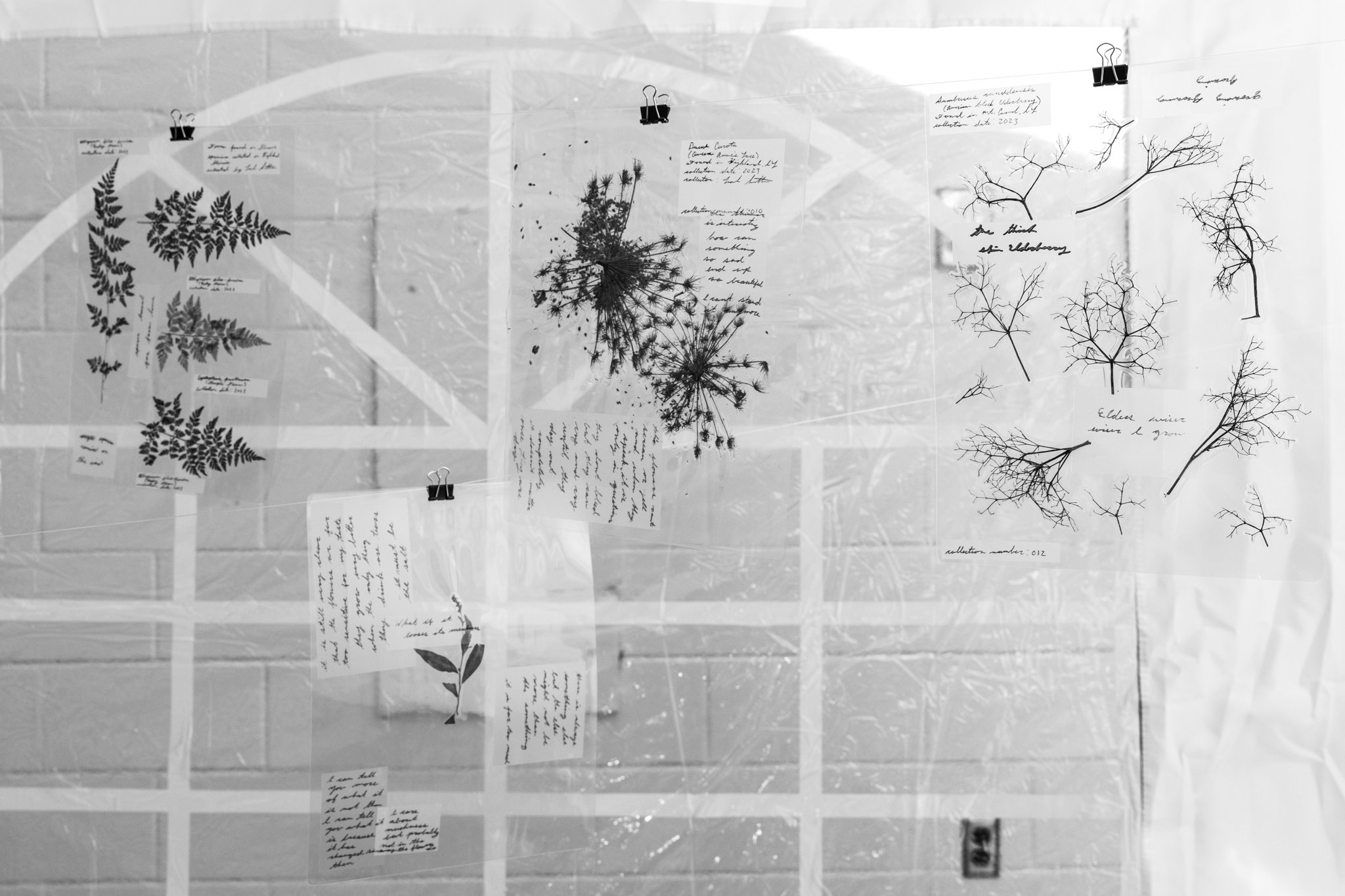

In essence, this real and unreal, organic and inorganic, inside and outside paradox is what the dichotomies present in Of Light and Shadow expose through their materiality. The makeup of Of Light and Shadow: dried plants and tea bags, manufactured specimen pins and laminated sheets, mechanical photography and text written by hand, all expose dichotomies between art and science, public and domestic, natural and artificial. By presenting these dichotomies through the juxtaposition of, for example, industrial, manufactured materials like the specimen pins and laminated sheets in opposition of the ephemeral object’s delicacy such as with the dried plant or the decaying teabag, this creates the same effect of the glasshouse, diorama or camera—a juxtaposition of the real and unreal through material objects that allow them to exist in the in-between.

The materiality and immateriality presented in the work, through natural history, shows both the passing and the halting of time. Through the laminated botanical specimens, a time is preserved and is juxtaposed with the fleeting moment of the images presented in the Looking-Glass Insects that constantly battle the fragility of their make up and the temporality of the material itself. The museological style of installation further adds to the accumulation of memory and time as it is compressed within the specimens displayed in Of Light and Shadow.

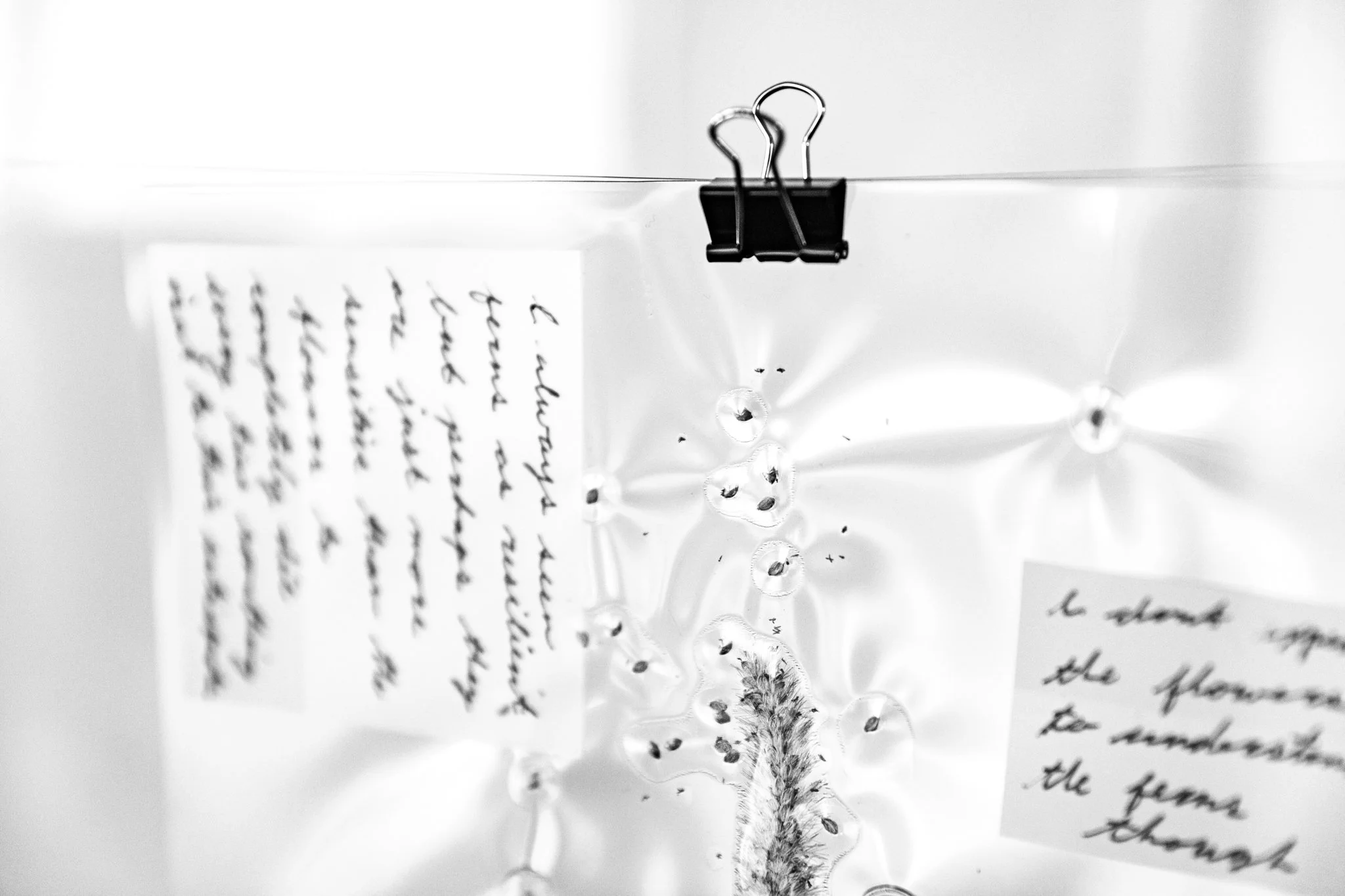

Looking-Glass Insects

While taxidermy acts as a bridge between a real animal and a fantastical recreation brought about by artistic rendering, so too do the Looking-Glass Insects bridge realism, through traditional mounting with specimen pins, and the fantastical, by placing mechanically reproduced photographs in a state of decay and materiality. It is also important to note that these displays of specimens are made “obsolete” due to advances in technology such as photography in the sphere of making their likeness available to the masses. A tribute to The Mock Turtle’s Story, in Looking-Glass Insects, the matboard is cut into tiny squares to be completely concealed by masking tape in which the specimen pins penetrate. The Looking-Glass Insects start to question their materiality and existence as objects within the in-between. With footholds in a state of decay and reproducibility, artificial and natural, the only authentic components of the Looking-Glass Insects are the originality of the handwritten babblings and the unique shapes and stains of the tea bags.

Before printing or writing on the tea bags, they first had to dry out and the botanical contents had to be dissected and removed. In The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Walter Benjamin compares a magician to a surgeon in saying that while a magician “heals a sick person by the laying on of hands; the surgeon cuts into the patient’s body.”19 Here, Benjamin claims that, while the magician keeps a distance but also maintains authority over the patient, the surgeon does the opposite and decreases the distance between himself and the patient by cutting directly into the body. He then uses this analogy to compare a painter to a cameraman. “The painter maintains in his work a natural distance from reality, the cameraman penetrates deeply into its web.”20 Similar to a specimen dissection, the tea bags would be cut down the middle seam in order to expose the interior of the specimen. This manner of penetrating directly into the tea bag is reminiscent of three mediums historically viewed as science—the arts of taxidermy, entomology, and photography—and transforms into a new dichotomy between art and science.

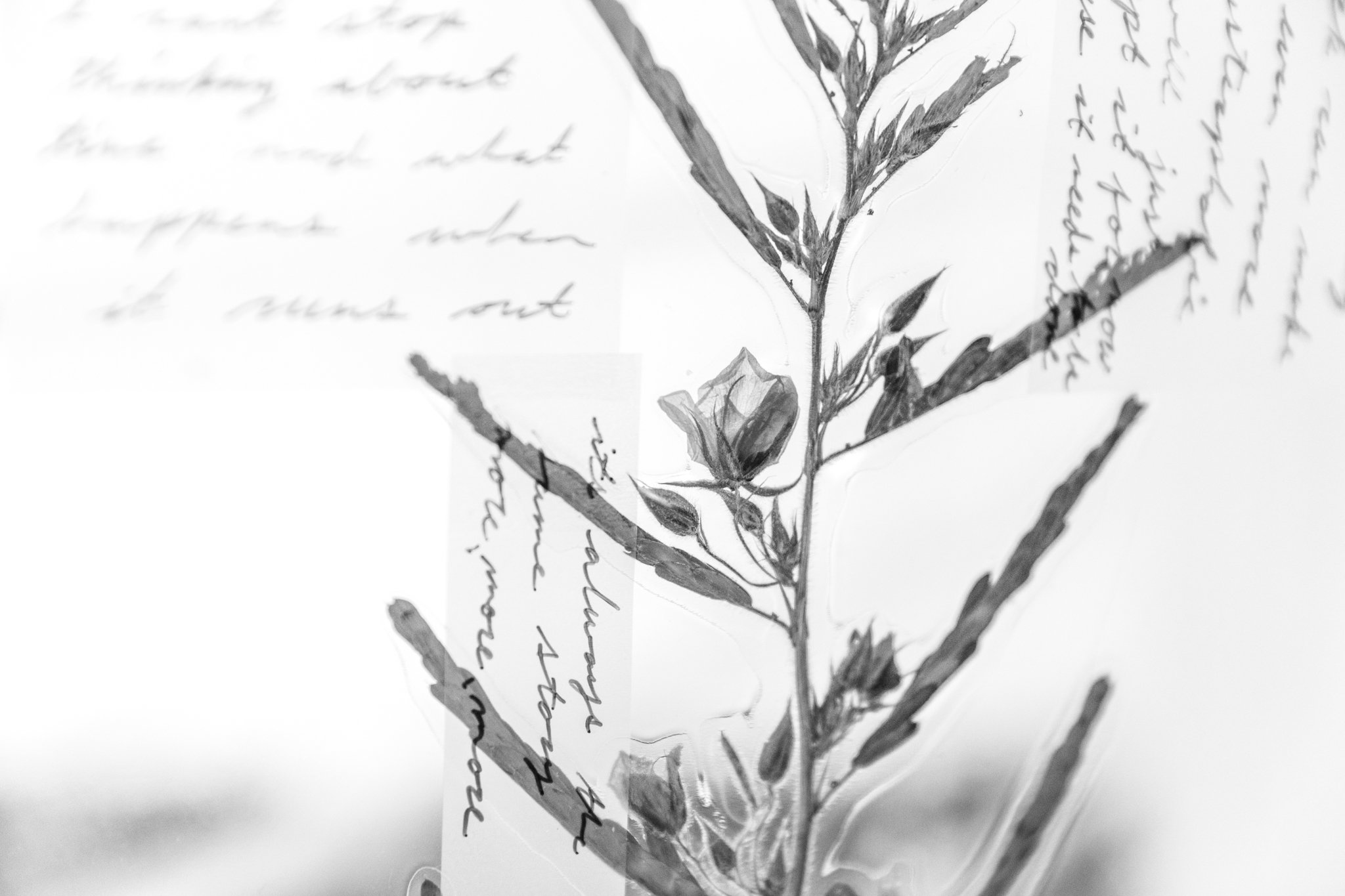

The Garden of Live Flowers

There is something fascinating about a plant that defies death and is instead preserved through both being dried and laminated. Similar to Looking-Glass Insects discussed previously, the laminating process brought up topics of the “idiomatic inability to tell the living from the dead”24 that both photography and the materiality of pressed plants produce. When cut from the mother, the plant loses the umbilical cord. It then has two options, it can shrivel up, die and decompose, or it can be pressed and preserved in a state that allows it to escape death.

Plastic laminate was the best material to use for the pressed plants in Of Light and Shadow, because of its refusal to disappear and its connections to the environment. It can also be noted that the appeal of availability of thermal laminate sheets is similar to the mass reproduction of plants discussed previously. In previous work, have discussed the importance of iron and glass in the Victorian era as being mass-produced and cost-effective materials for large-scale work such as the Crystal Palace for the Great Exhibition in 1851. The cost-effective and readily available material of the 21st century being plastic is a testament to the ways in which capitalism continues to strive toward the most cost-effective form being much cheaper than iron and glass ever was in the Victorian era.

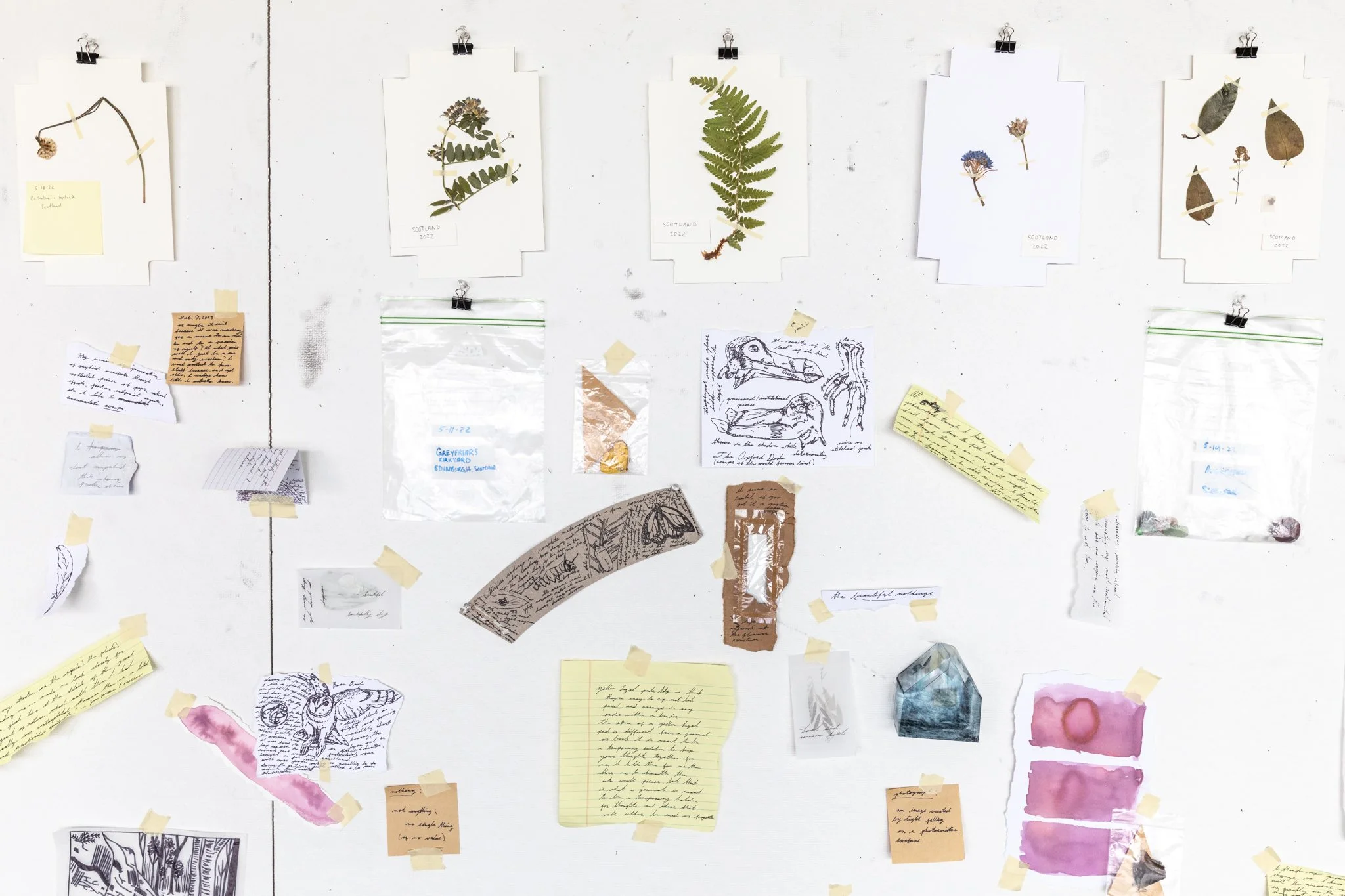

The Mock-Turtle’s Story

I was seven and making field journals. I didn’t call them “field journals” because I had not learned about words that carried that meaning. There was a particular red, clothbound journal that I called my Book of Everything. It's very clever, really, it was a book and it was filled with everything; a safe place to keep track of anything that I found interesting. It was new to me. The information was new to me. The idea of a Book of Everything seemed like a genius idea because no one had ever done it—I was seven. The contents ranged from animal facts to studying the phases of the moon to pressing plants within the pages. There was even a point in time when I was attempting to teach myself hieroglyphs. It wasn’t all academic though, I was still a child; there were IHOP kid’s menus in there too. Scraps. Fascinating to a child. The Book of Everything was one of my inspirations to create this fragmented installation titled The Mock Turtle’s Story. In Alice in Wonderland, Alice comes to find a Gryphon and a Mock Turtle where the Mock Turtle begins to tell Alice stories about his education—a clear parody of education within Lewis Carrol’s time. The chapter on the Mock Turtle begins with the Duchess telling Alice, “‘Be what you would seem to be’— or if you’d like it put more simply—’Never imagine yourself not to be otherwise than what it might appear to others that what you were or might have been was not otherwise than what you had been would have appeared to them to be otherwise.’”5 This greatly foreshadows the issues that Alice has with semantics relating to the Mock Turtle’s stories surrounding his education. The first instance is when the Mock Turtle tells her that his teacher in the sea was an old Turtle, but they called him Tortise. Alice questions him on this and the Mock Turtle’s response is that ‘Tortise’ is what he was taught to call him. Though this form of classification seems absurd, it is an uncanny analogy to how I view my journey to creating Of Light and Shadow. As the ‘in between’ I am simply a person with an insatiable curiosity that won’t be limited to one discipline or mode of working.